“Cold mush dreams”

The cinematic adaptation of Cheryl Strayed‘s memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail seems to be getting pigeonholed hard as being solely a tale of female empowerment. It most definitely is, but I’m not sure critics should necessarily call it a day with such a generic categorization. There’s a deeper draw to the author’s solo, one thousand mile journey along the Pacific Crest that hits at a human level way beyond gender. Was Into the Wild only thought of as a tale of male empowerment against the excess of his own affluent society? Perhaps it was, but it never seemed like a knock as it does this time around. Sean Penn‘s film wore it as a badge of honor and if we’re going to distill Wild to such terms I hope it does too.

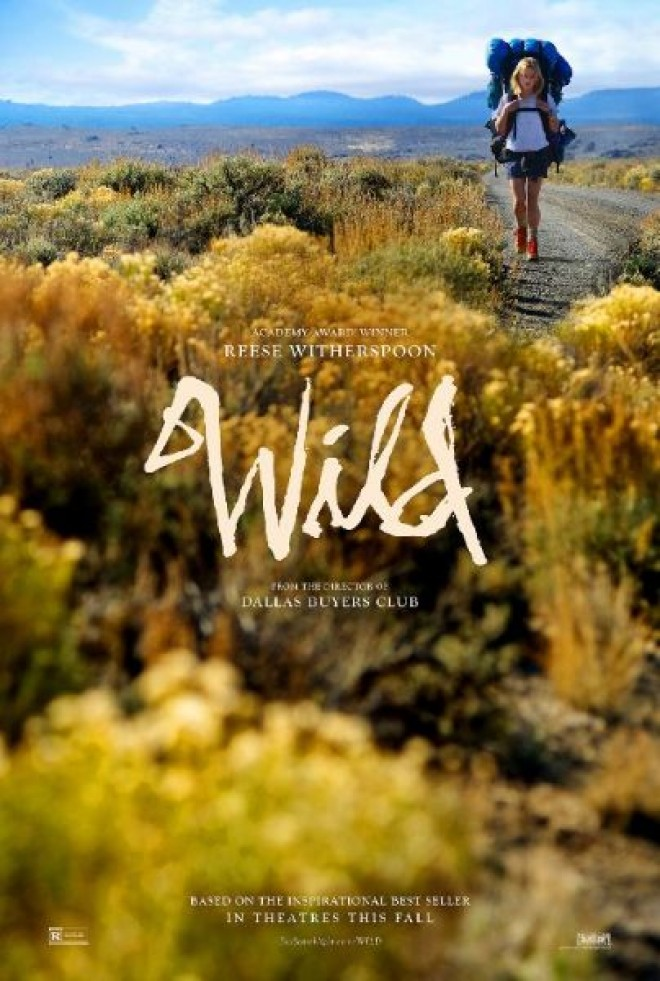

The most recent installation in the true-life story told via daily countdown portion of director Jean-Marc Vallée‘s oeuvre (Dallas Buyers Club being the first), Wild is equal parts Into the Wild andThe Way—Emilio Estevez‘s passion project about a father hiking the Camino de Santiago to reconnect with the son he lost long before starting. I dare say it’s better than both too in content and orchestration due to a perfect storm of dedicated talent. Reese Witherspoon delivers a stirring performance as Strayed spanning multiple years via flashbacks (years all at least a decade in her rearview mirror yet handled well just the same); Nick Hornby a script tying together Cheryl’s many tragic hardships testing her constantly; and Vallée a deft visual style projecting everything as aggressive blinks of past and present psychologically baiting her to quit.

But quitting is the one thing she cannot do no matter how arduous the trail or memories placing her upon it. She wants to stop and her first day almost renders the whole film moot, but she continues forward. The voice providing her strength is her mother Bobbi (Laura Dern), coming to Cheryl in waves of recollection and déjà vu. A person she held as a hero and whose death destroyed any spark of life she once possessed. They were inseparable, connected deeper than blood the moment a six-year old girl was made to compassionately daub an open wound slashed over her mom’s eye due to an abusive father back home. Bobbi took her daughter and son (Leif played by Keene McRae older) away, devoted to them until also being able to live for herself alongside both.

The way Vallée and Hornby tell it—perhaps Strayed’s own device from her book, I haven’t read it—is light years more potent than simply portraying the linear progression of Cheryl from studious wife to drug-fueled sexual promiscuity to broken soul willing to forsake everything to rediscover “the woman her mother raised”. We need to meet her in the middle yanking the nail off her big toe and screaming into the wide expanse of nature surrounding her. We must accept her struggle and see the pain in her eyes mixed with unwavering determination to wonder at what caused it. It’d be easy to chalk it up to a thankless marriage and dead-end life, but that’s not the case. Cheryl had everything she ever wanted and then the grounding force at its center was taken away forever.

Wild is therefore a film about grief—something we can all relate to no matter our chromosomes. It’s about the courage to get up from our lowest point and do whatever it takes to get back on track. It’s about those who remain, love in every form whether friend (Gaby Hoffmann‘s no nonsense Aimee), wronged ex-husband (Thomas Sadoski‘s still caring Paul), or equals journeying the wilderness alone for their own reasons (Kevin Rankin‘s Greg). But most of all it deals with the notion that no one who leaves this earth is ever truly gone. Everything we cherished and despised about them remains in our hearts, rising to the surface because of a song on the radio or a rush of adrenaline caused by fear. Sometimes it very well may be their inability to disappear that makes matters worse.

And this is the human aspect that hit me so profoundly. It was the anger Witherspoon brings out—anger in her loss, in the failed optimism Bobbi never stopped expressing, and in herself for the multiple ways in which she shattered her own life. Watching as the frames onscreen flip from the gaunt and dirty face of present-day Cheryl to the writhing naked form of a few months previously to the little girl long ago with her father’s fist threatening a knuckle sandwich, the filmmakers manufacture a minimalistic sensory overload with her screams and the music of her youth. We become transported with her to those memories both good and bad, disjointed and jumbled for emotional relevance as opposed to thematic. Cheryl is trying to put herself back in sequence despite being unsure if doing so is possible.

Above the sound design and editing, however, this film is nothing without Witherspoon’s transformation into Strayed. She definitely found a connection to the material, optioning the book and signing on to produce and star in it from the beginning. She dove headfirst despite the R-rated language and nudity providing a contrast to the wholesome woman Hollywood has crafted to be her celebrity persona for the masses. Able to turn from wary to thankful on a dime opposite W. Earl Brown‘s Frank or cautious to downright scared against Charles Baker‘s T.J., we understand the strength necessary to do what she’s doing. Strayed’s experience is an inspiration to all, telling us to conquer our fears even if what we fear is personal happiness. We all must scream uncensored and without judgment at some point in our lives. This is hers.

Score: 9/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 115 minutes | Release Date: December 5th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Fox Searchlight Pictures

Director(s): Jean-Marc Vallée

Writer(s): Nick Hornby / Cheryl Strayed (memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail)