“I knew I shouldn’t have had that champagne”

There’s little scarier in this world than a debilitating disease like Alzheimer’s. You may initially feel a sentiment as shared by the titular Alice (Julianne Moore) in Still Alice to be hyperbolic, but the thought that cancer could be a better option is an extreme worth considering. We’d all hope to never have either effect ourselves or our families, but the prospect of losing health does in a certain way seem more appealing than losing one’s self. Because that’s what Alzheimer’s does: it takes your memories, everything you’ve accumulated over your lifespan. Everything that you are gone disappears in a blink. The greater your knowledge, the higher your intellect, and the quantity of experiences you’ve shared all add up to an increased rate of deterioration due to possessing more to forget.

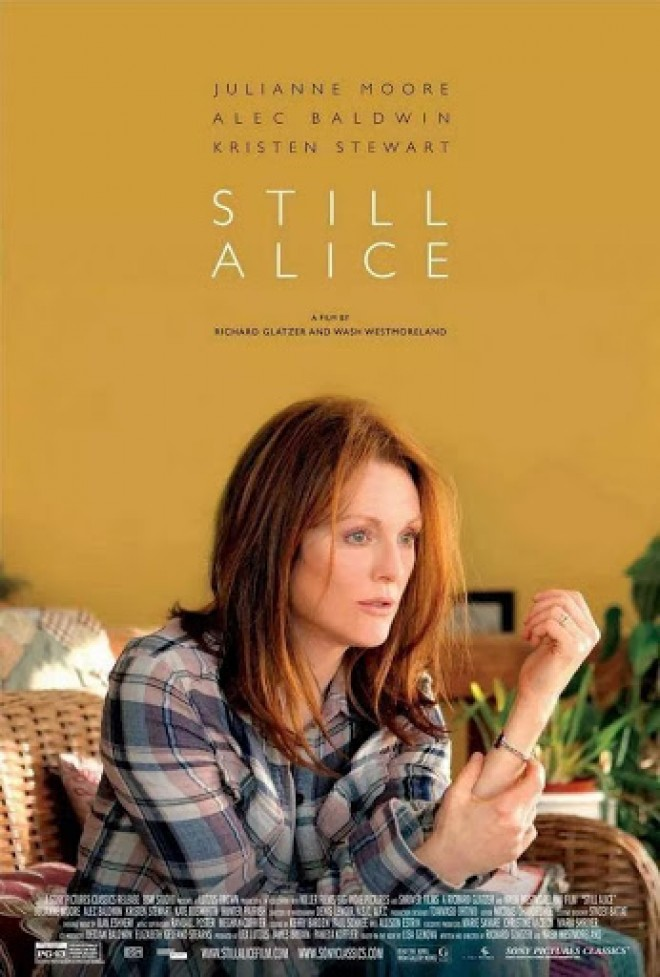

Sarah Polley crafted what might be the end all be all of Alzheimer’s movies in Away From Her. It works so well because everything that happens comes across as intimately personal. It’s as much about the afflicted as it is the spouse trying to cope with his own loss of the person he had hoped to die beside. The biggest challenge for Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland‘s adaptation of Lisa Genova‘s novel therefore becomes juggling the myriad characters they’ve placed onscreen. With three children, a husband, a neurologist, and additions like babies and significant others, there arises a surplus of peripheral distractions to take us away from the subject at hand. At moments it almost seems as though it’s begging us to sympathize more with the people around Alice than her.

This is saying something considering Moore’s phenomenal turn. In all honesty, everyone is great—enough so that they take a bit of the spotlight away. The filmmakers use many visual tricks with blurry to in-focus transitions as well as invisible jump cuts through time to disorient us alongside Alice wading through the unknown, two stylistic choices that work wonders towards their goals. The reason for this is that both maneuvers directly correlate to this central character. Alice foggily listens as her family makes decisions about her future. She has sparks of clarity believing only hours have past when it’s actually been months. And with emotional sequences such as “Butterfly”—you’ll understand when it happens—Moore wrecks us further with every step backwards.

It’s understandable why the filmmakers and Genova go in this direction. They are seeking to bring Alzheimer’s into the public consciousness in as much an educational way as emotional. This is why we watch Alice’s husband John (Alec Baldwin) and their kids Anna (Kate Bosworth), Tom (Hunter Parrish), and Lydia (Kristen Stewart) learn about the disease with her. By giving them the tools to comprehend, the film in turn provides us the same. Family also goes hand in hand with the severity of the form of Alzheimer’s Alice suffers from—one additional tragic detail to wake the public up to a horror faced by so many. And while it may be simpler to dismiss the elderly as having lived long and fruitful lives, early onset is a whole other story.

So, sadly, the very thing Still Alice sets out to do becomes its downfall from being a singular piece of cinema that transcends its material. It tries so hard to hit various authentic checkpoints in the journey of a patient that it makes her specific pathway generic rather than personal. The condensing of time gives it a sense of urgency, but it also conditions us to know every scene holds a profound moment of pain. The only reason we see Christmas dinner is for Alice to forget Tom’s new girlfriend’s name. The only reason we see the birth of Anna’s kids is so the question of whether she can be trusted to hold them will crop up. Rather than share quiet moments, we’re given difficult and loud ones in quick succession. I became numb as a result.

By the end I didn’t care what choices John or the kids made or of their moral crises in regards to the potential of leaving Alice behind. Some of them were powerfully drawn on the surface, but without any semblance of surprise they all occurred as though part of a script. The only real thing became Alice herself and Moore’s alternatingly delicate and volatile portrayal. Watching her reach for words just out of her grasp, breakdown in tears when others guard themselves and refuse to empathize with her plight, or genuinely thank Stewart’s Lydia for showing the compassion to ask how she’s doing rather than pretend to know are what makes this film necessary. And it is necessary as well as a great venue to spark conversation.

It merely tries to do too much. That may be nitpicking, but I can’t gloss over its reality. While I can imagine people who’ve experienced a loved one falling prey to the disease seeing themselves in these characters, recalling similar exchanges they made, I was kept at a distance. Whereas Away From Her shined a light on romance, love, and loss that went beyond Alzheimer’s itself, Still Alice is forever bound to its circumstances. Alzheimer’s isn’t merely the reason why certain common things that happen to all families are happening to the Howlands—it’s the sun they revolve around. That’s a limiting viewpoint. Yes it ensures we know Alzheimer’s is the culprit and in need of a solution, but it also takes away some of its potentially heartfelt universality.

Score: 7/10

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 101 minutes | Release Date: December 5th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Director(s): Richard Glatzer & Wash Westmoreland

Writer(s): Richard Glatzer & Wash Westmoreland / Lisa Genova (novel)