“I was lucky enough to admire my lover”

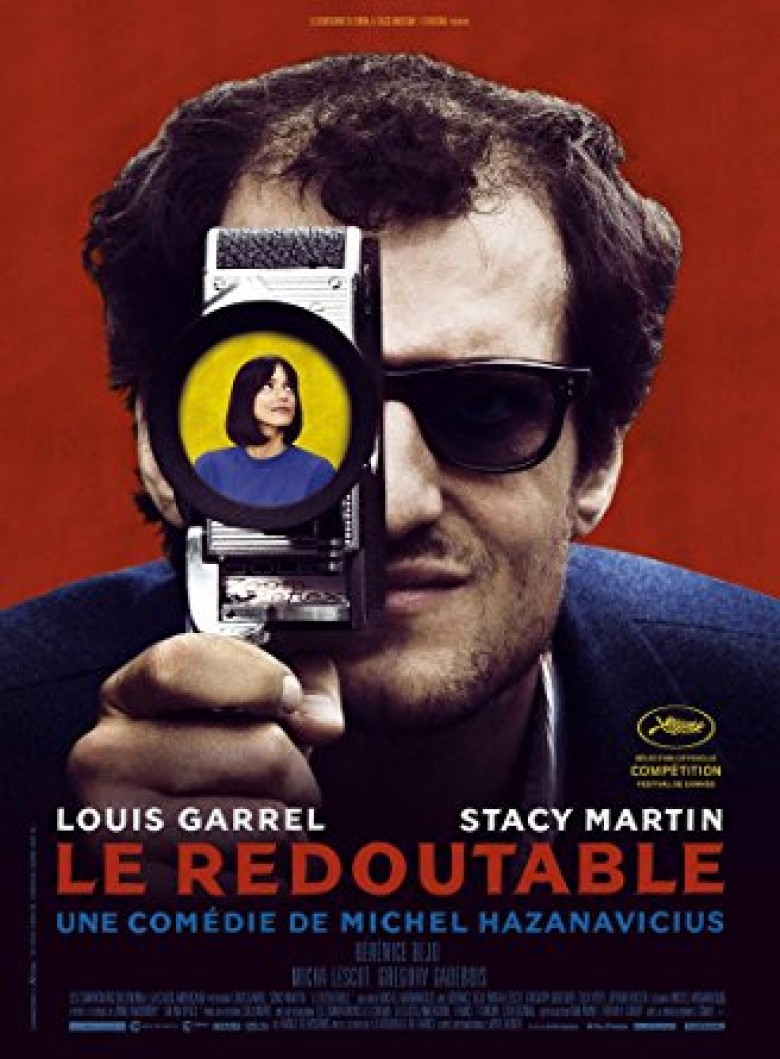

We’re introduced to Emile (Marc Fraize) halfway through Michel Hazanavicius‘ Le Redoubtable [Godard Mon Amour]. He’s a local Frenchman with a car and the means to procure enough gas to drive an argumentative Jean-Luc Godard (Louis Garrel), his wife Anne Wiazemsky (Stacy Martin), and their friends (Micha Lescot‘s Bamban, Bérénice Bejo‘s Michèle, and Grégory Gadebois‘ Michel Cournet) home from Cannes. His inclusion moves the film forward from place to place while also providing a stand-in for we the viewers caught watching Godard’s mid-life crisis unfold. He holds his tongue until believing the moment is right to interject a layperson’s opinion, hoping to help calm rising tempers. It only fuels more anger to the point where he cautiously checks to ensure everyone is asleep before exhaling his next breath.

I felt like Emile for the film’s entirety: this unassuming person thrust into the middle of a chaotic fight without sufficient enough information to fully comprehend what was happening. To be fair, I’m not sure the players in this fight knew exactly what was going on besides the fact that they had to yell and flail to specifically attempt to cancel out the yelling and flailing coming from the person next to them. Adapted from Wiazemsky‘s book Un an après—Hazanavicius even has Godard speak in voiceover that it was she who decided to tell this chapter of their lives to the world—it obviously shines the French auteur in a conflicted light, one for which nobody would question the veracity. I therefore only wonder about the point.

Is it merely to show a genius unraveling? Is it to explain why Godard’s later work never lived up to his early masterpieces? Is it to show how politics can warp an artist’s mind? What about age and the jealousies coming along for the ride? It could very well be all of the above, but it doesn’t matter because that’s noise overshadowed by the repetition of self-implosion. As revolution rages, Godard feels his insecurities and futility. He criticizes the bourgeoisie because he knows he is bourgeois and he hates himself. He hates that he’s becoming irrelevant and decides to disown his previous movies (Breathless, Contempt, and Pierrot le fou among them) to prove his worth within the impending political war. He doesn’t realize doing so confirms his irrelevancy.

The result is a boring slog that follows his steady descent into caricature. We listen to him scream “Godard is dead, long live Godard” at least three times and laugh with the young revolutionaries slowly realizing that their hero is a washed-up self-parody hack. Some of the comedy works by being absurdly broad (the constant breaking of Jean-Luc’s glasses being met with exasperation meant to mock his being “old” at thirty-seven) while some earns crickets from tongue-in-cheek tiredness (having Garrel look directly at us when complaining how actors are so stupid that they’ll take a paycheck to verbally admit so onscreen). The plot documents Godard’s evolution towards the Dziga Vertov Group, but it does so with farce rather than history. Its subject becomes a joke and thus uninteresting.

This would be okay if we received more scenes from Anne’s point-of-view. It’s her story after all. So why not let her be the focus? Let Godard embrace the role of hyperbolic Eeyore because that vantage comes from the eyes of the woman he let down. That’s the only way we could ever treat this depiction as authentic because the portrayal comes across as misguided otherwise. We can neither sympathize with Godard nor despise him since nothing feels real. It’s as though we’re supposed to take the film as an exercise wherein we’re watching Garrel and Martin play make-believe. This isn’t Godard and Wiazemsky; it’s an expensively produced skit poking fun at cinema’s self-seriousness. It exposes the ugliness of ego and the sycophantic praise of idolators.

Just because those skits work effectively at times to lambast their targets individually, however, doesn’t mean stringing them together within the trajectory of a real-life romance’s dissolution is automatically successful. They would be better served as bits of a comedy special—a Monthy Python does French New Wave sort of thing. Then we could always be ready for the next on-the-nose laugh that’s derisive as reverential to a subject the jokester respects. As it is now we simply scratch our heads that Hazanavicius so willingly turns from an absurd act by Garrel to an emotionally potent reaction by Martin. She does a great job exposing Wiazemsky’s confliction and disappointment, but the performance is lost once a single cut to her smiling face mocks our honest heartbreak.

Rather than be the person we should care about, Anne becomes a pawn in Godard’s head. He wields her as a weapon meant for self-harm, but we don’t pity his struggle. If anything we pray he will put himself out of his misery because then we too would be free. This Jean-Luc is a self-absorbed baby feigning modesty when someone hands him a microphone only to rile everyone up with bigoted nonsense he believes is transcendent thinking. And we watch this shadow through the lens of his greatest achievements with Hazanavicius paying homage to Godard’s style via tracking shots, subtitled subtitles, and aesthetic color inversions. But just like the character, these flourishes ring hollow. Martin and Garrel nakedly talking about unnecessary nudity isn’t smart, it’s easy.

Godard Mon Amour plays like an all-over-the-place pastiche of biography and roast that says little. It’s the tale of a rich intellectual sticking his head so far up his behind that it ends up back on his shoulders. It asks us to take his celebrity at face value and his revulsion towards it as evidence of self-loathing. Jean-Luc makes so many missteps here that we begin to wonder if he simply got lucky early before out-staying his welcome. That doesn’t mean he isn’t a cinematic master who reinvented the medium. It just shows he’s human and undeserving of blind allegiance like the rest of us. We experience with Anne how our naïve, smitten eyes eventually find the clarity to see the much uglier truth hidden beneath unrealistic fantasy.

Score: 4/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 107 minutes | Release Date: September 13th, 2017 (France)

Studio: StudioCanal / Cohen Media Group

Director(s): Michel Hazanavicius

Writer(s): Michel Hazanavicius / Anne Wiazemsky (novel Un an après)