“A fastball on the outside corner”

Apparently, many people have been docking points from Denzel Washington‘s latest directorial effort Fences, calling it “too theatrical.” Well, that’s hard to avoid when you’re dealing with August Wilson‘s Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning play and its wall-to-wall dialogue touching upon love, responsibility, race, and politics on an emotionally resonant level far beyond much of what Hollywood delivers cinematically. I’ve personally never held a stagey aesthetic against a film as long as the performances prop up the script’s location shortcomings and ensure that every word uttered is done so with pure authenticity. Mike Nichols accomplished this with his debut Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (one of my all-time favorite plays and films) and Denzel does the same in this intimate 1950s-era Pittsburgh backyard.

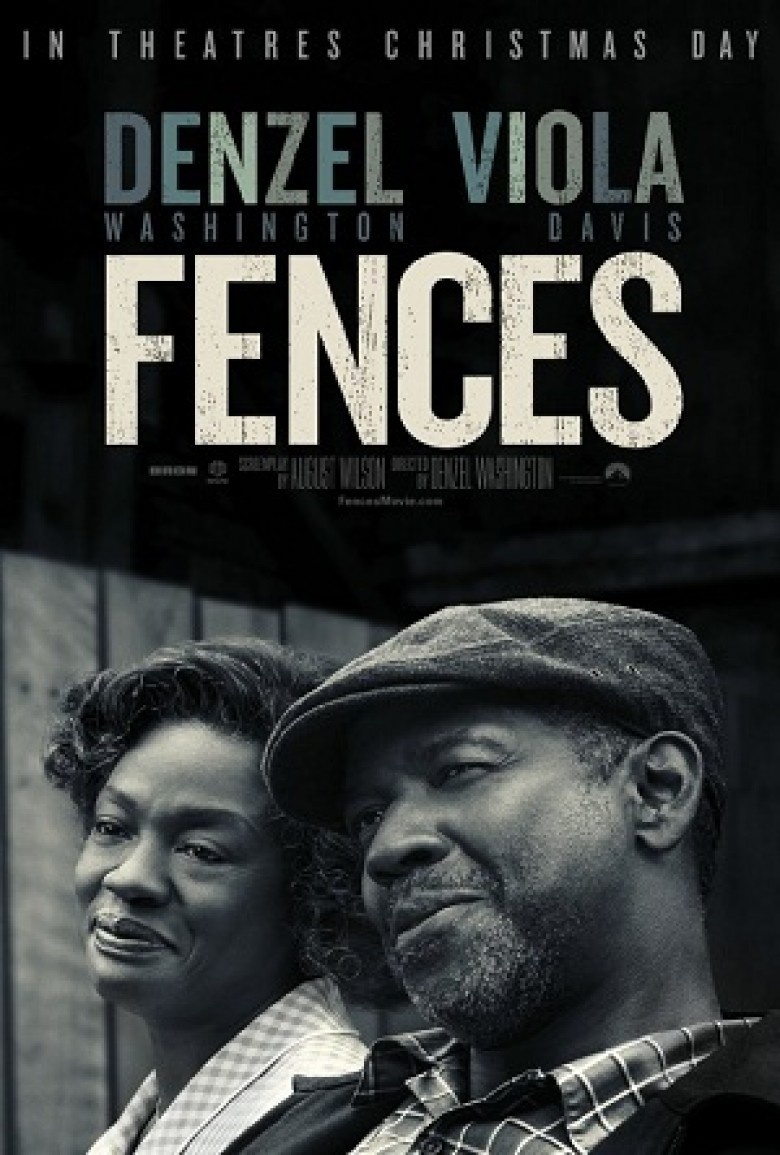

The play originated in 1983 with an amazing cast consisting of James Earl Jones, Mary Alice, Frankie Faison, and Courtney B. Vance. Wilson wanted to bring it to the big screen, too, if only he could find an African American director to take the helm. That sadly didn’t happen within his lifetime (the playwright passed away in 2005), but he drafted a screenplay nonetheless in the hope that it would. Fast-forward to 2010, with Washington and Viola Davis staging a revival winning them both Tony Awards along with the play, and it’s no surprise that they reunited five years later to carry its Broadway appeal into multiplexes across the country. Stephen McKinley Henderson, Mykelti Williamson, and Russell Hornsby agreed to reprise their roles and the result is nothing short of an acting clinic.

What’s funny is that the best parts for me are the ones you couldn’t get onstage. So much of the almost two-and-a-half hour runtime of Fences deals with two or three characters in heated conversation, while others may or may not be silently listening, in obvious discomfort as they try not to get involved. There’s a lot of hypocrisy going on—a lot of supposed compassion by way of self-interest, wherein the man leading the charge (Washington’s Troy Maxson) refuses to see how times were changing enough to realize he is the spitting image of his father and that his son Cory (Jovan Adepo) looks just like him. It’s great seeing veiled cringes or muted looks of acquiescence from those in the frame, but it’s something completely different seeing them off-screen.

It doesn’t happen often, but Washington and cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen (who does so much with very confined spaces) sometimes provide eavesdroppers behind walls. We see the fear in Gabe’s (Williamson) expression as he sits at the table while Troy shatters his wife Rose’s (Davis) world. We feel Lyons’ (Hornsby) empathy and pain as he lowers himself into a kitchen chair while his half-brother Cory struggles to mine below the surface of how their father treated them: with tough love, not a lack of it. These moments say so much without saying anything because there’s an inherent complexity to every action on display. We’re privy to a circuitous cycle created by impossible circumstances. Every time we think Troy learned something, the opposite is revealed to be the case.

There are Cory’s collegiate football hopes being dashed by his father. The boy believes Troy’s refusal to be happy is rooted in jealousy and he’s half correct. It’s not jealousy that Cory may prove better than his old man, but the jealousy that he has an opportunity to backstop the volatile choice of professional sports with a trade in case it all implodes. There’s the notion that, despite everything, Troy went through (the details of which are left to Wilson’s magnificently written, hyperbolic and fantasy-tinged stories his lead speaks with a gin-soaked smile), he came out with a devoted wife and a life worth living. His best friend Jim Bono (Henderson) saw this turn of events and latched on until it happened to him, too.

But nothing is ever as it seems and nothing is ever perfect in a “Leave It to Beaver” way regardless of race or economic standing. The Troys of the world aren’t wired to explain their motivations beyond extreme psychological punishments pushing their sons farther away. The Troys of the world are never satisfied with a “good life" like Bono when distractions continue to promise something a little bit better instead. And the idea that life stifles your ambitions and dreams isn’t yours and yours alone. You can be selfish to the point of risking everything good that ever happened to you, but never seek pity. Never ask for understanding from the person who stood by you despite experiencing the same crisis of identity each day without acting upon it.

In this regard, Washington—no matter how amazing in this role of hidden depths as a husband, father, son, and friend—is far less revelatory than is Davis as Rose. Here’s a woman who epitomizes the 1950s housewife with a public face of strength and joy against a private one of cautious optimism and quiet suffering. We watch her set Troy straight when his stories get out of hand or too “macho.” We watch her undying love for this man despite knowing he has some demons that he simply won’t let her help alleviate. But she isn’t some caricature bolstering harmful stereotypes of what a “wife” should be. She’s allowed her moment to speak her mind and admit choices she willingly made with regret and those now supplying her with renewed vitality.

Rose is the glue that precariously holds this family together for better or worse, seeing the good in each cog even if it’s often difficult to look past the bad. We feel a release resting on the horizon during her early scenes with each disapproving glance when Troy’s ego gets the better of his humanity. We just aren’t quite prepared for the catalyst’s full scope or the visceral power of her reaction. Davis and Washington handle the resulting control shift beautifully—their interactions with each other reverses despite the fact nothing on the surface changes. She grows stronger as he accepts his waning moral superiority as false. Rose might not receive what she had hoped, but she rises to the occasion anyway. Troy, on the other hand, becomes exactly what he promised he never would.

No matter how much respect we may lose for this blue-collar garbage collector, we cannot deny that he didn’t accomplish what he sacrificed his very self to do. Life throws the Maxson clan more curveballs than most (just look at Gabe’s reward for serving his country) and Troy strikes out more than his fair share, but this era measures success by one’s children. The lesson here (beyond its supernaturally-tinged epilogue) is that all we can ever aspire to do is give our kids the best parts of ourselves. We give them what we didn’t have and we pray they don’t fall into the same traps that we fell into. If we can’t learn from our own mistakes, hopefully they can. Maybe then the pain wrought will be worth it.

Score: 9/10

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 138 minutes | Release Date: December 25th, 2016 (USA)

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Director(s): Denzel Washington

Writer(s): August Wilson / August Wilson (play)