“Your life slips away from you, you know?”

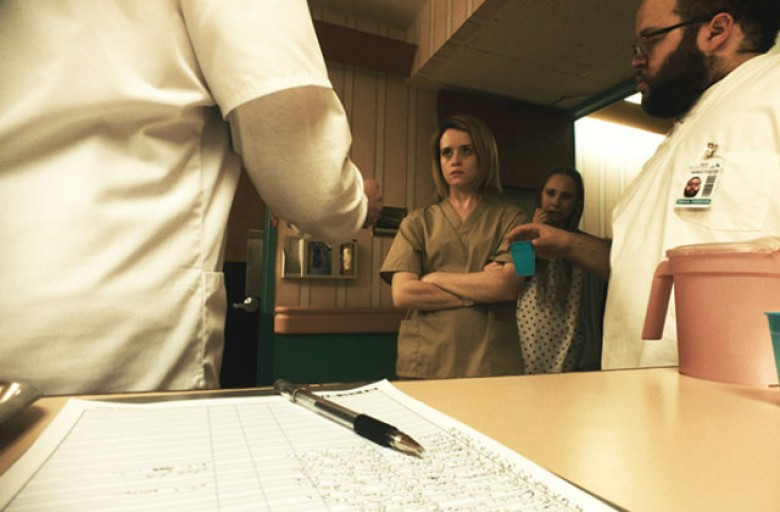

The tagline to Steven Soderbergh‘s Unsane reads as follows: “Is she or isn’t she?” Its context stems from Sawyer Valentini (Claire Foy) being presented as an unreliable narrator. She’s picked up her life and moved it from Boston to Pennsylvania to escape the troubles of her past—namely, a stalker whose lack of boundaries instilled enough fear to make her see him in places where he wasn’t. We understand that this struggle is real because of a one-night stand that ends with her scream after the man she brings home changes identity into her assailant for a split-second. She seeks help, finds a counselor and believes a breakthrough can occur. But that optimism disappears when she discovers that she’s been duped into committing herself to the psych ward.

Did she or didn’t she, though? What if Sawyer only thinks she was duped? What if she really signed in while fully cognizant before another episode brought on another fit of paranoid delusions? Is she an adjusted woman with understandable post-traumatic stress? Or is she a violently explosive personality ready to throw down with whomever gets in her way? And when she starts seeing that same predator in the face of a hospital orderly (Joshua Leonard), is her mind playing tricks on her? Has this yet as of yet unknown figure ignored his restraining order to find her across state lines? Or are her hallucinations growing more and more dangerous for herself and those around her? Eventually she calls her mother (Amy Irving) and reveals how she never told her about the stalker. Did he ever exist?

These are the questions about which the tagline hints. These are the mysteries we hope Soderbergh will unravel in whatever experimental way the director sees fit. And considering he has chosen an iPhone 7 as his camera, the sky really is the limit as far as what his always-unique mind can think up. Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer‘s script doesn’t even have to be good as long as it possesses the latitude for him to have fun because his visuals and technological ingenuity can transcend the plot. The problem therefore arises when Soderbergh forgets to do anything. If he shoots this film on a cellphone but does nothing to prove it couldn’t have been shot in any other way, it becomes a gimmick that its problematic story cannot hide behind.

For all those hyperbolically exclaiming that Unsane is a game-changer: go watch Tangerine. For those saying that they had no clue about what might happen next: watch more suspense thrillers and better horror. I say these things because there’s absolutely nothing of value to be had from the experience onscreen besides enjoying a highly effective performance by Foy. She’s giving this project more than it deserves because we do ultimately believe that she believes she may no longer have a grasp on reality. Unfortunately we don’t believe it ourselves as members of the audience. We don’t believe because Soderbergh uses very direct visual cues to reveal every string the script contains. As soon as you leave Sawyer’s vantage point, her role as unreliable narrator ceases. She becomes a character within a transparent plot.

The first quarter of the film is great because all we know is what Sawyer sees. Soderbergh introduces her delusions with immediacy and her paranoia with an authentic unease as the world literally closes in around her with the stroke of a pen. There’s a crazy, malicious bunkmate (Juno Temple‘s Violet) and a suspiciously calm voice of reason in the bed across the room (Jay Pharaoh‘s Nate Hoffman). The atmosphere is thick with uncertainty and Sawyer snaps more than once upon “seeing” her nightmare right in front of her. But then we leave her behind. We start viewing what Nate does outside of her gaze. We’re made to watch conversations between hospital staff that she isn’t privy to. The filmmakers show their cards.

All potential for surprise disappears. Any maneuver to reveal a “twist” becomes a punch line because it seems as though the filmmakers still think it’s a twist. Sawyer’s sanity proves to be a red herring, as the truth is exposed with matter-of-fact cinematic language despite the fact that the film continues to falsely manufacture intrigue. So any time that something happens to make us start questioning reality, we don’t. Why? Because reality has been firmly established. Instead, we’re made to endure obvious machinations that are either repetitive or redundant. It makes Leonard’s performance seem preposterous by pretending that the gig isn’t up. It makes us wonder if Soderbergh is laughing, showing just how dumb some thrillers are by making his own even dumber. Why else would he distractedly give his BFF a cameo?

But Soderbergh never fully leans into the silliness. He never overtly says he’s having a laugh at the expense of those who believe that outlandishly clumsy social commentary (there’s a subplot about health agencies imprisoning patients to drain their insurance money) like this is earnestly hoping to spark change. That’s not to say that he doesn’t have ample opportunity, however. The film could have ended on a gloriously insane bit of hyper-violent nihilism to really put a cherry on top, and yet it consciously holds back as though any of the reductive and sometimes offense depictions of mental illness and PTSD are to be seen as sympathetic rather than exploitative. Either Soderbergh chickened out or he fell prey to his own delusion that this script was somehow bolder than it is.

Score: 4/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 97 minutes | Release Date: March 23rd, 2018 (USA)

Studio: Fingerprint Releasing / Bleecker Street Media

Director(s): Steven Soderbergh

Writer(s): Jonathan Bernstein & James Greer