At the mere mention of a strike, I take to my bed. This has become a family joke. Whenever I get that shock of cortisol and adrenaline, I pull the covers over my head and hide for as long as it takes.

“Take to my bed” implies a movie actress in a black and white film, lounging in a sheer peignoir, a princess telephone and a box of bonbons half eaten on her nightstand. For me, “taking to my bed” looks more like an old possum, belly up and struck dumb by the fear of what might happen next.

I snuggle deep into the comforter and cover my ears with pillows. I want to block out whatever lies beyond the confines of my bed.

The voice of my dead grandfather revives me from the strike stupor. I rely on my dead relatives. If the inner-child within has a voice, then there must be a grandparent, aunt, uncle or cousin who get a say, too. My dead relatives are still so much a part of me that they rattle my spine and shout louder in my ear from the grave than they did when they were alive. Only now, it’s from the inside out rather than the outside in. And my grandfather, who was dubbed The Night Hawk while working nights at Bethlehem Steel, would never have brooked this kind of dead-possum-taking-to-my-bed over a strike.

Of all my chattering dead relatives, he shows up the least. He was quiet in life and so he is in death. Occasionally, I hear him tsk-tsk when I reach for an overpriced chicken or a single roll of toilet paper at the supermarket. Sometimes, I can hear the shuffle of a deck of cards behind me when I watch an old movie on TV. Two good ways to summon the voices of dead relatives: do what they loved to do; or go against their code of conduct.

My grandfather liked bold, headstrong, straight-talking women, like his wife and daughters.

“You get yourself downstairs and take care of your family,” he says in a baritone which exudes finality.

“I didn’t grow up with you,” I retort. “I don’t know how to take care of my family during a strike”.

My parents, a nurse and a teacher, at one time or another, both held union cards, but never was there mention of a strike that would threaten their livelihood. My husband works as a field tech for Verizon. In the thirteen years we have been married, this is the second strike. The last one was over before I could get my bearings.

My grandfather was a proud and active member of the United Steelworkers. He fought in the 30s, 40s and 50s for a living wage and humane working conditions. The threat of a strike came every few years. My mother remembers the fear and worry that gripped her household before and during a strike. In our large Catholic family, a strike meant it was time to sacrifice for the common good. They networked to take care of each other and their communities. Workers were financially forced out of their homes to live with parents and extended family. Block parties, church dinners and cheap government cheese helped provide for families’ needs.

But, this is a different era and it demands a different kind of support.

My grandfather’s voice softens, the way it always did when he wanted to encourage me to do the right thing.

“Nobody knows just what to do during a strike. Take care of your family like you always do”.

I climb out of the bed and stand at the top of the stairs. An electrical charge ricochets off each family member and zaps them at the same time. So he can hear over the clamor of the kids, my husband, Dave, has the television news blaring. I hear the air pressure and pop of a nerf gun, which my ten year old son, Sam, knows he is not supposed to shoot in the house. My four-year-old yells, throws toys or hits his brother who screams, “Mooooom, Cal is hitting me."

I worry that being a stay-at-home mom has become a liability. I wonder how many bills can be put off and how many will demand payment. I need to get my resume together and find a job. The first amenity to go will be cable TV and never mind my morning latte. I can feel myself doing an about-face, inching my way back to the bed.

“It’s going to be okay, honey,” my grandfather whispers.

I love these imaginary conversations with my dead relatives, but at this moment I want to lean into him. I want to feel his arms around me in that grandfatherly embrace that erases the years and responsibilities.

My husband calls out, “Are you up?”

I’m so proud. The strike has energized him. He is so like my grandfather - honorable, loyal, with a penchant for straight-talking women and an eye for the common good.

I yell down, “Is there any Easter chocolate left?” (my next comfort measure).

And then, I take those first few tentative steps down the stairs.

To learn more about the Verizon strike and why workers have chosen this option, please visit the CWA District 1 website here.

And, if you are so inclined, here are seven ways to encourage and support this strike:

HONK - If you drive by a picket line, tap on your horn. A friendly beep shows support and encourages workers.

SIGN their petition - Stand with Verizon Workers on Strike

BAKE a casserole - I joked about this with my friends on social media. Baking casseroles is very old school. But I encourage you to donate gift cards for gas, supermarkets, pizza, etc. Last week on the picket line, a young girl presented a box of donuts to my husband and said, “My mom wanted me to give you this because she supports your cause.” Her mom beeped and waved from the car.

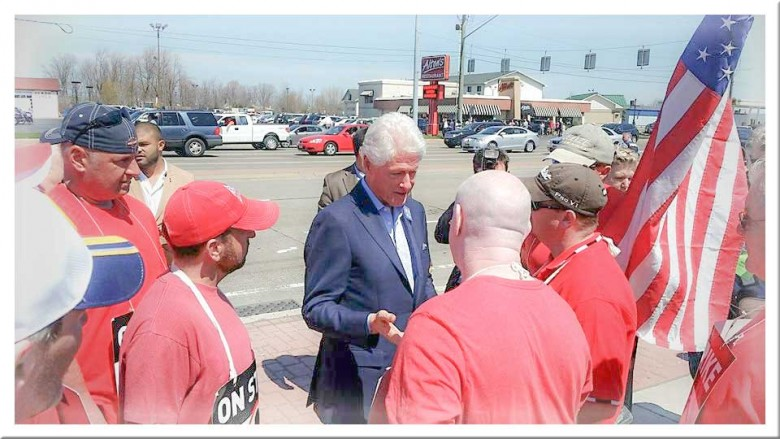

WALK - Don a red shirt and attend a rally or walk with workers. Find out here when and where.

SOCIAL MEDIA - like, tweet, retweet, and share links on your favorite platform in support of the strike.

SHARE INFORMATION - regarding temporary employment that can help feed families during the strike.

DO NOT CROSS PICKET LINES - “It (the strike) is the strongest action workers can take in an economy that is otherwise stacked against them.” ~ Billy McMahon (read the full article here). As workers, we are your community.

My father has organized our family food store. He rallied Sam to help with meal planning and he explained to Sam that there are two sides in a strike: one side has loads of money, high priced lawyers and jobs, but on our side of the strike, we only have each other.

A reflection my grandfather might have voiced himself.